Michalina Kułakowska

Aleksandra Solińska-Nowak

20 min read

12.03.2025

PARATUS:

Key Takeaways from the Serious Games Workshops for Stakeholders

Introduction

Serious games are becoming vital tools for training, problem-solving, and decision-making processes—especially for first and second responders.

In the PARATUS project, we emphasized the importance of co-designing serious games with stakeholders to create meaningful and impactful learning experiences. Games can encourage out-of-the-box thinking, free from social constraints or other limitations, but integrating these tools into disaster preparedness requires careful planning.

Instead of offering pre-designed tools, we involved stakeholders in shaping game mechanics and narratives to reflect real-world multi-hazard scenarios. This approach ensured that simulations resonated with real-world challenges and provided a risk-free environment for experimentation while fostering collaboration across disciplines.

It has to be remembered that serious game development requires an iterative approach that involves feedback loops and adaptation to be effective. This is why, over two years, we conducted multiple co-design workshops and testing sessions—online and in-person—engaging public administration, researchers, and emergency responders. These sessions helped refine the tools and align them with stakeholder realities and learning objectives.

While collected feedback highlighted areas for improvement, the co-design process deepened engagement and enhanced learning outcomes. This publication shares key insights from our journey, starting future discussions on integrating serious games into multi-hazard preparedness programs.

How We Designed the PARATUS Serious Game

Developing a serious game for disaster risk reduction is not just about creating an engaging experience—it’s about ensuring scientific rigor, stakeholder relevance, and real-world applicability. To achieve this, we followed the CompleCSus framework, a structured methodology that integrates risk assessment, stakeholder input, and iterative development.

In the first phase, we conducted a literature review on Disaster Risk Management (DRM) and serious game methodologies while consulting experts and stakeholders to identify real-world challenges. This helped us select disaster scenarios that accurately reflect multi-hazard risk environments.

In the second phase, we moved to game structuring and prototyping. We developed player roles, decision-making mechanics, and scenario structures, refined through Learning Labs. The design was also informed by best practices from the study “An Overview of Serious Games for Disaster Risk Management“, incorporating key elements such as realistic scenario development, social and interactive learning, and structured debriefing sessions. By integrating Design Thinking, Agile Development, and the ADDIE Model, we ensured a user-centered, iterative approach that prioritizes usability and engagement.

Workshop formats and their impact on feedback-gathering methods:

- General Assembly Workshops: a more formal setting with multiple stakeholders in attendance required time limits on discussions. Nevertheless, this format effectively showcased how serious games could be integrated into larger conferences or gatherings.

- Online Workshops allowed broad participation (removing geographical barriers) but entailed technical challenges. Virtual settings encouraged peer-to-peer feedback via chat and breakout rooms, underscoring the adaptability of serious games in virtual settings.

Face-to-Face Workshops enabled immersive experiences with rich, real-time feedback on group dynamics and decision-making.

Case Studies: Bucharest & Alps Workshops

As part of the PARATUS project, two major stakeholder workshops took place in 2024, highlighting contextual differences that shaped the discussions and priorities of disaster preparedness:

- Bucharest Workshop (Urban Seismic Risks): Focused on emergency response and inter-agency coordination – a necessity in a region vulnerable to earthquakes and flood-induced cascading disasters. Participants included representatives from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the National Emergency Services, and key defense, transportation, and urban planning decision-makers.

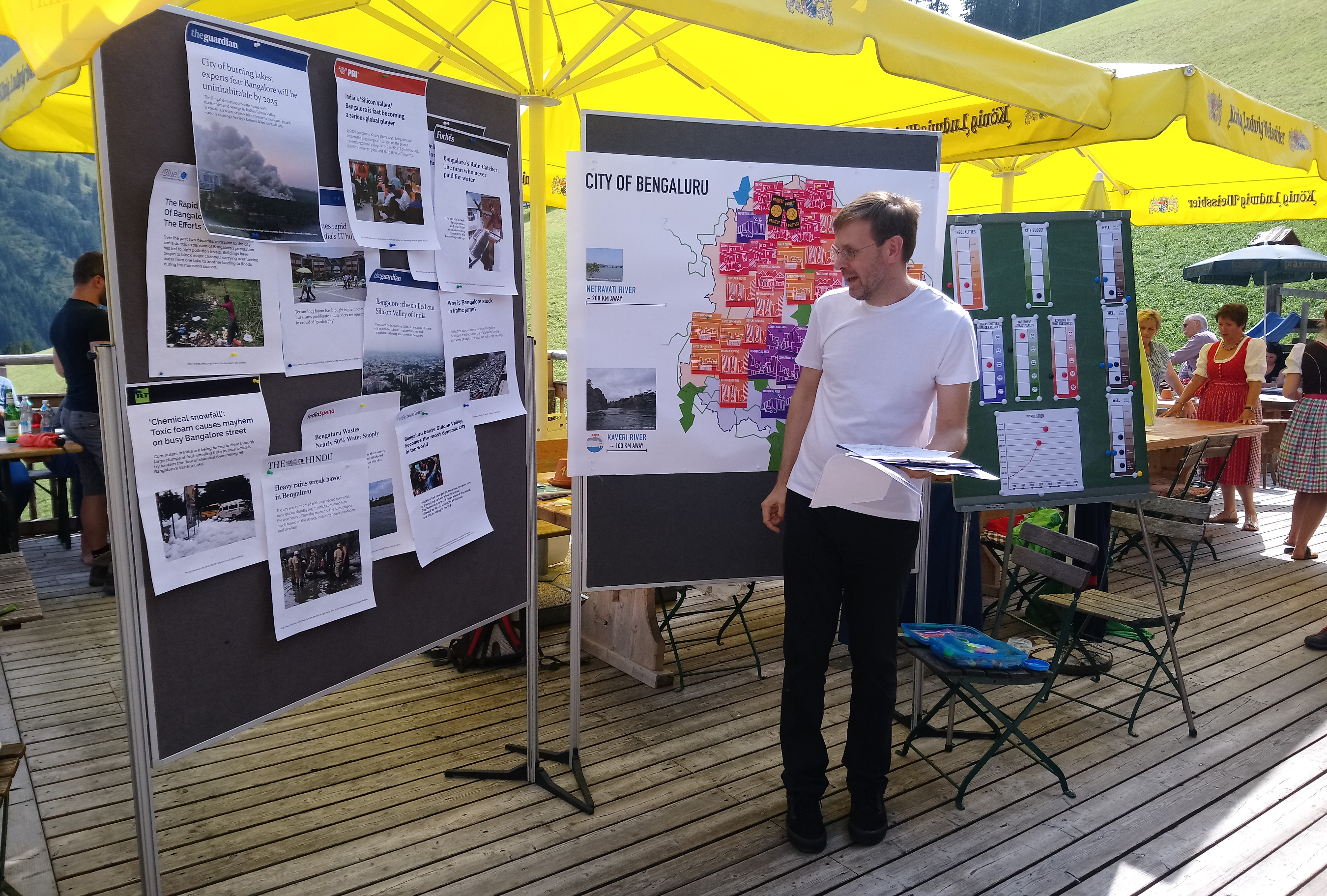

- Alps Workshop (Infrastructure Resilience): Explored long-term adaptation strategies for resilient transport corridors, which are prone to landslides, floods, and rockfalls. Stakeholders from transport authorities, local governments, environmental agencies, and infrastructure operators engaged in the discussions.

Serious Games as a Common Tool, Different Applications

Both workshops reinforced the value of serious games for decision-making and resilience planning. Yet, the application of the tool in each case varied:

- In Bucharest, the serious game was designed to simulate a multi-agency crisis scenario, allowing stakeholders to test emergency response strategies and assess decision-making under pressure. The session provided valuable insights into risk perception, communication breakdowns, and coordination challenges faced during real disasters.

- The Alps workshop integrated the serious game into scenario planning and infrastructure risk assessment. Instead of focusing on crisis response, participants explored long-term adaptation strategies—balancing economic needs, environmental constraints, and disaster mitigation. The game allowed stakeholders to negotiate and test different resilience-building measures, similar to the real-world trade-offs faced in managing trans-Alpine transport routes.

Despite the differences in how the two workshops were designed and delivered, the core mission remained the same: to equip first and second responders with the tools to navigate complex disaster scenarios in a controlled yet highly realistic setting.

Through interactive simulations, participants experienced cascading disasters and deepened their understanding of multi-hazard risks and impact chains. Scenario-based learning embedded real-world DRM challenges, fostering stakeholder engagement and realistic decision-making. The games also allowed participants to test adaptation and mitigation strategies under uncertainty, honing their ability to make quick yet informed decisions in crises. With case studies drawn from diverse socio-economic and geographic contexts, the simulations were designed to be scalable and adaptable, ensuring their relevance across different regions and risk landscapes.

Evaluation and key takeaways

To assess the tools co-created in the PARATUS project, we developed evaluation surveys and an observation protocol, which allowed us to capture stakeholder perspectives on game design, usability, learning impact, and their attitudes towards the approach. The final evaluation framework, including insights from co-development workshops and case studies, will constitute one of the PARATUS deliverables.

The use of a mix of observation protocols with evaluation surveys during workshops minimized bias from self-reported feedback and provided deeper qualitative insights into group dynamics, engagement levels, and spontaneous reactions.

Evaluation surveys/ players’ feedback:

The key takeaways from the surveys and feedback collected include:

(1) Co-design approach according to participants:

- relies on stakeholders’ engagement

- broadens stakeholder participation in proposal stages

- enables working at one’s own pace.

Conclusion: The co-design approach enhances both the learning and the development process, and it is advised to use it while planning tools for multi-stakeholder processes.

(2) Keeping the balance between engaging game elements and realism is challenging:

- Engagement: Participants wanted interactive and dynamic elements (storyline, visuals) that would keep them immersed and motivated, including unexpected challenges mirroring real crises.

- Realism: Some criticized the game’s limits in replicating emergency scenarios’ high-stress, unpredictable nature. However, this tension is inherent in serious games. Perfect realism is nearly impossible; the goal is to simulate core decision-making processes under pressure.

Conclusion: Future iterations of the game can focus on refining scenario details—e.g., by using more realistic visual cues or introducing time constraints—to engage the audience and enable actionable learning.

(3) The iterative design process ensured that key learning objectives were met. Despite some critical feedback on game elements (e.g. lack of realism), players claimed that they:

- improved communication skills with emphasis put on clearer task delegation and more effective decision-making.

- enhanced situational awareness by quickly assessing environments, synthesizing new data, and adjusting their response plans.

- improved adaptive problem-solving: teams that pivoted mid-simulation showed greater flexibility in real-world tasks.

Conclusion: Criticism doesn’t always signal failure—frustration can drive deeper reflection and better skill retention. Despite frustrations or a perceived lack of realism (feedback on game elements), participants demonstrated improved strategy and coordination skills, proving the game’s positive impact.

Structured Observation for Deeper Insights

Instead of relying solely on surveys and post-session feedback, we used a structured observation protocol to document real-time player behavior:

- Decision-making Patterns: Who took the lead? Did the team collaborate effectively or did one voice dominate?

- Emotional Responses: Did participants display visible signs of stress or confusion? How did they cope with it?

- Communication Flow: Which channels of communication were used most effectively (voice, text, gestures)? Were instructions clear or ambiguous?

- Adaptability: How quickly did teams shift strategies in the face of changing game scenarios?

Cross-referencing these observations with surveys/feedback provided a detailed view of participant experience and team dynamics, helping us refine game complexity and debrief strategies.

Key takeaways:

(1) Collaborative Decision-Making is Essential: teams that communicated consistently and pooled their knowledge performed better. Reinforcing open communication channels is a crucial step in any crisis.

(2) Flexibility Trumps Perfection: quick, adaptable decisions proved more effective than waiting for the perfect plan.

(3) Feedback Should Be Nuanced: criticism of design elements doesn’t mean training is ineffective; it often signals areas for improving game elements, while the core learning outcomes remain intact.

(4) Multiple Delivery Methods Enhance Reach: combining online and in-person sessions expands access and limits travel costs, especially for those in remote or resource-limited settings.

(5) Debriefs Solidify Learning: guided reflections after gameplay reinforce lessons and help identify training gaps.

The feedback we received is invaluable for the next phase of development and training. Here are a few improvements we plan to implement:

- Enhanced Realism: We will introduce more dynamic scenarios—such as sudden weather changes or shifting on-site hazards—to mimic the unpredictability of real emergencies.

- User Interface Upgrades: Addressing player feedback on navigation and clarity will help maintain engagement without sacrificing educational depth.

- Focused Debriefs: Incorporating breakout sessions specifically for reflection, with guiding questions, should deepen the learning experience.

- Modular Design: Splitting the game into shorter, scenario-specific modules can allow responders with varying roles (firefighters, paramedics, etc.) to tackle the most relevant segments.

Conclusion

The Serious Games Workshop series was both rewarding and challenging. Participant feedback—calling for more realism or interface improvements—will help us refine future training. However, our observations confirmed that key learning goals, especially in communication, situational awareness, and adaptive decision-making, were successfully met.

For first and second responders, serious games offer more than static training; they support continuous learning and reflection. By integrating feedback into iterative design improvements, future workshops can better meet user expectations, while maintaining their strong learning impact for frontline risk management.