Amanda Anthony

20 min read

08.04.2019

What Macron Would Do Differently If He Could Go Back In Time

It’s May 2017. We see an elated Emmanuel Macron, celebrating his presidential victory, his platform focused on making the government more efficient and including green initiatives aimed at helping France reduce its dependency on nuclear and fossil fuels. In his acceptance speech, he says he understands the “rage, anxiety and doubt” simmering in the country and that he plans to use his five years healing the divisions.

It’s November 2018. Thousands of people line the streets in Paris and beyond wearing “yellow vests”, protesting the proposed rise in the diesel fuel tax. They claim that his policies make it hard to live in France. They claim he is out of touch with the struggles of workers.

Even though many protestors support energy transition, the simple framing and brute implementation of the tax on diesel simply did not take into account all the tradeoffs that come with moving to renewable energy, nor did it examine the emotional effects of yet another policy being imposed upon an already burdened populace.

Wishing for a do-over

Macron must be wishing he could go back in time and do it over. It is, of course, too late for that – he is currently relegated to crisis management and image rebuilding. However, the idea of “looking into the future” is something he should consider before taking up the issue of carbon taxes and other climate change policies again.

This isn’t some kind of “Minority Report” fantasy: It is a fruitful time for immersive, forward-looking approaches to problem-solving. From Henry Mintzberg’s work on “seeing first” and “doing first” in strategy development, to Stuart Darcy’s experiential futures and Richard Duke and Jac Guert’s policy exercises, we now have less linear and more active ways of exploring the future before it comes. Among these strategies is the use of social simulation, aka policy or serious games.

Energy Transition Game

Using social simulation to see the future

Social simulation helps players bring their ideas of the future to life. As they adopt roles and implement their solutions, they begin to “see” how creativity is necessary for addressing so-called “wicked problems.” They feel ownership of their decisions and the results in a way that the more linear thought exercises of traditional scenario planning do not enable.

Players who have used Energy Transition Game, our social simulation on the transition to low-emission energy sources, often come in with a determination – like Macron – to take action. For many, it’s a very logical process: implement the tax, reduce carbon emissions, success!

What they often do not realize is that each well-intentioned idea has a number of different possible outcomes based on both the decisions made and the decision makers. Making consumers bear the real cost of energy production, including pollution mitigation, may work as planned. Alternatively, the policy may be implemented too quickly and clumsily, and be followed by protests, opposition and a significant decline in public support. There may be even 100 other possible results, based on who is at the table, whose views are considered, when and how fast decisions are made and many other factors.

That is why the critical moment for using simulation or other types of experiential scenarios is well before policy implementation, as Margaret Thatcher learned with her “Working for Patients” idea.

Social simulation in practice

In the famous “Rubber Windmill” simulation, the would-be policy administrators challenged themselves to come up with and “implement” a number of possible future scenarios to reform Britain’s National Health Service. By role-playing several potential situations, they hoped to identify traps, blind spots and other challenges and prepare accordingly. What the simulation showed was that the reforms as initially proposed were unfeasible, sending its proponents back to the drawing board.

Where else could simulation have been useful? For starters: Managing the Flint, Michigan, water crisis, Brexit, or the 2015 European refugee crisis. If policymakers had stepped back from politicking and invested the time in exploring the future through simulation, they may have been able to take better decisions.

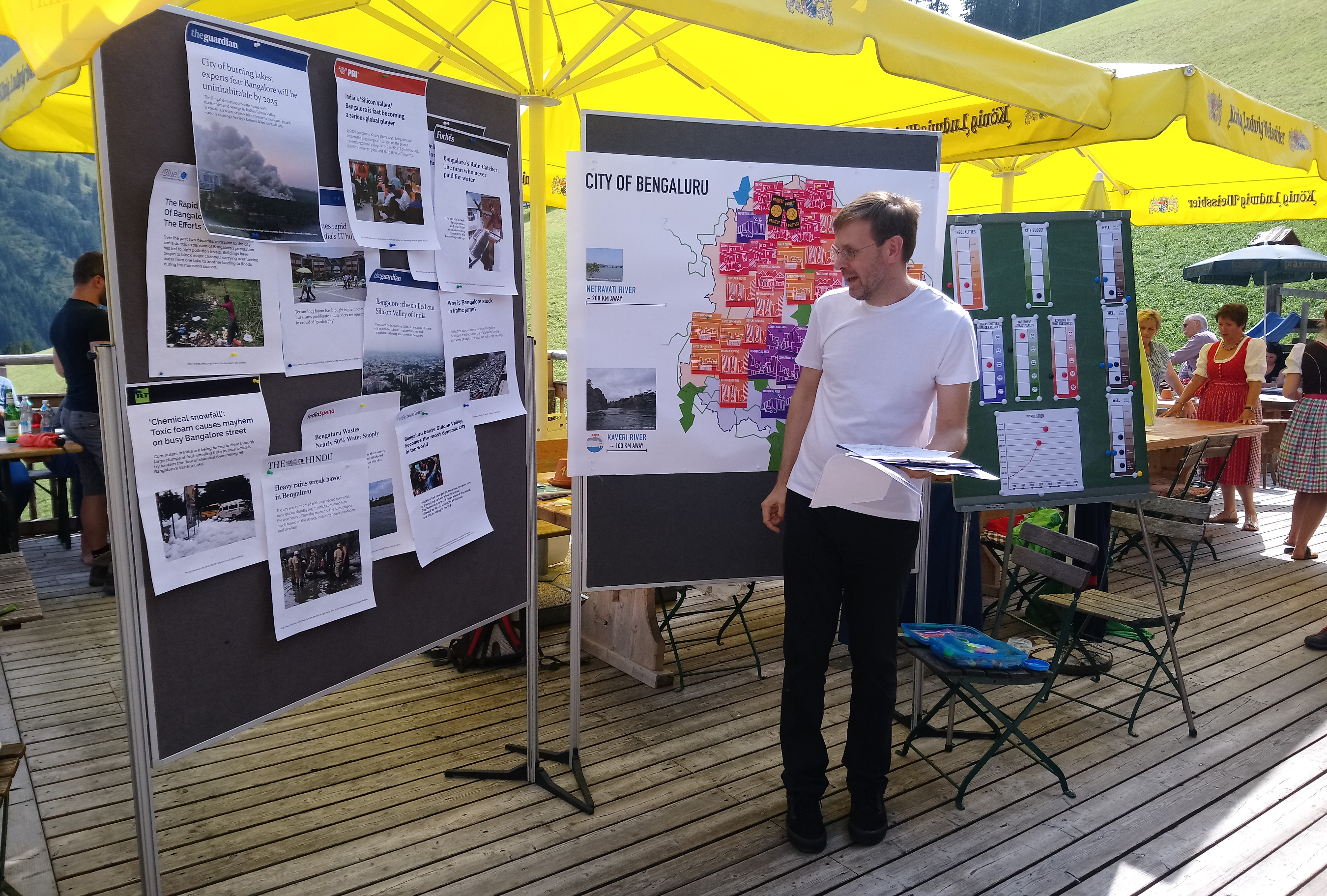

The World\'s Future

Time-traveling to The World’s Future

Going forward, other leaders should put their ideas and assumptions about the potential crises of tomorrow into practice using immersive exercises. A particularly good example of this concerns the Sustainable Development Goals, which are built on a complex system with many interconnections. Using The World’s Future would help policymakers and others with a stake in SDG implementation travel 40-50 years ahead in time and see the interplay of their decisions on the whole ecosystem – not just the effects within their borders.

As momentum gathers around ideas like the Green New Deal and debate continues on migration policy, discussions are taking place about how the as-yet-undefined specifics of goals, strategy, and implementation should look. If we are serious about achieving sustainability and if advocates want their policies to stick, they must be able to find a level of consensus on goals, somehow reconciling diverse worldviews. Incorporating social simulation in their planning would enable them to “see” many possible outcomes and more confidently and creatively shape the future.